The Journey

Story of Ladakh Pashmina

Pashmina originates from the Changthang region of Eastern Ladakh. The story of Pashmina is the story of this region.

The raw fibre comes from the western extension of the Tibetan plateau, an important high-altitude grazing system and is grown by nomadic and semi-nomadic herders who brave the harshest weather conditions.

Changpa pastoralists rear a diversity of livestock including horse, yak, sheep and goat.

Domestic goats are the main source of Ladakh Pashmina.

The Process

Herding

Changra goats are reared in high-altitude cold deserts amid unforgiving weather conditions. The intense cold, highly elevated landscape is perfectly suitable for producing this high-quality fibre. Nomadic communities of Changthang face tremendous hardships to sustain traditional herding practices, which are increasingly becoming more challenging due to various socioeconomic and environmental factors.

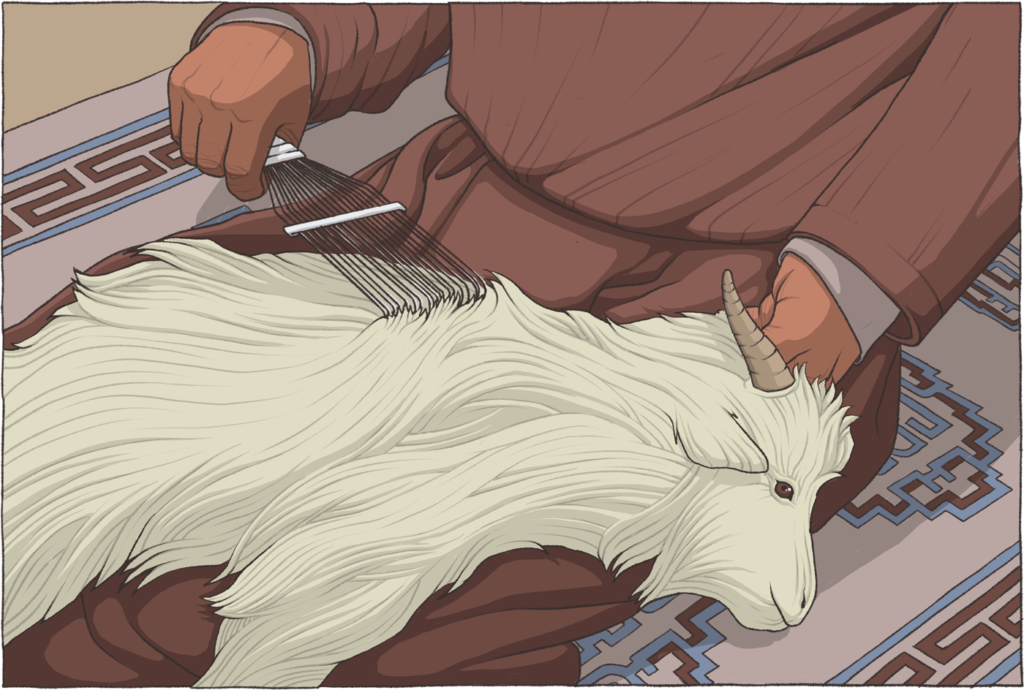

Harvesting and Combing

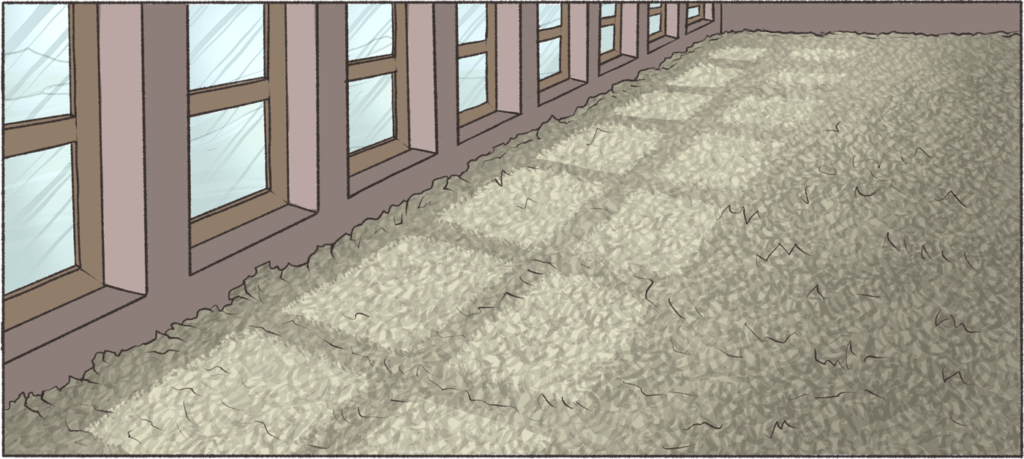

Wool is obtained once a year when the goats naturally start shedding their wool. This wool is harvested by combing out the fleece from the goat’s underbelly. Herders traditionally use a wooden comb with large bristles to carefully harvest this precious fibre – creating a unique nomadic culture around this practice.

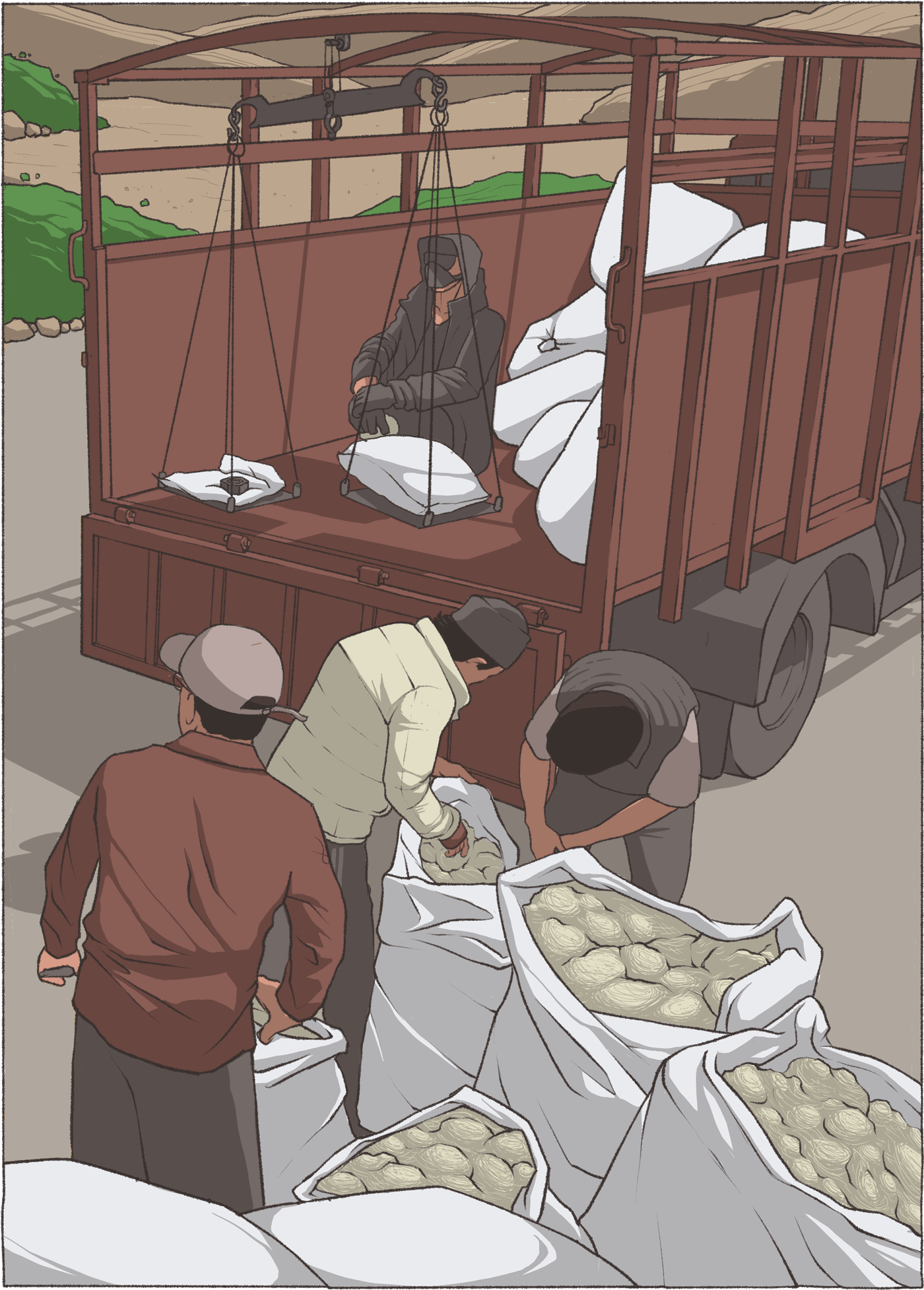

Procurement

The Herder’s Cooperative directly procures raw Pashmina fibre from herders in Changthang. The Cooperative provides a fair and competitive price for raw Pashmina and ensures a transparent procurement process. The Cooperative procures 40 to 70% of the total produce each year.

Sorting

All of the raw wool collected is manually colour-sorted. There are three natural wool colours of the Pashmina goat – white, black and light brown. Sorting is an important step to avoid mixing wools of different colours. The sorting can be done either at the village level or at the Cooperative’s facility in Leh.

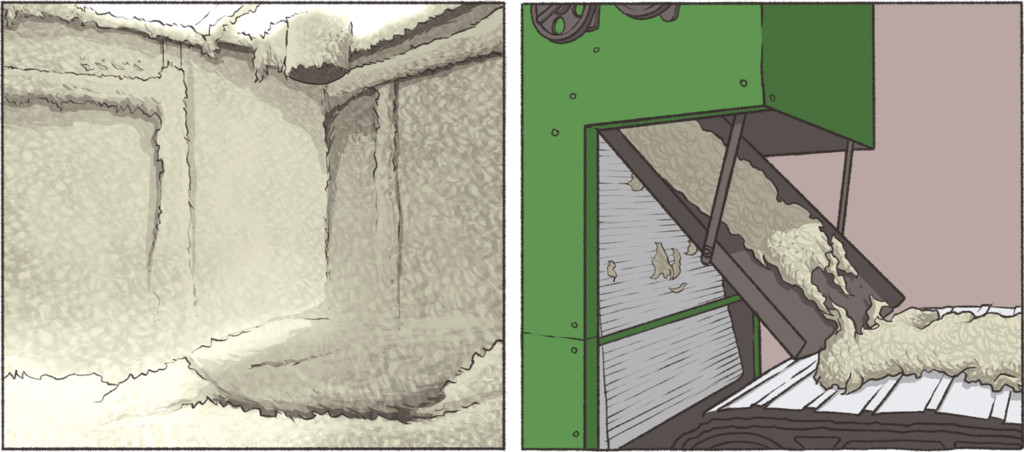

Scouring

Bundles of raw wool are put in a de-hairing machine where it goes through various stages of cleaning. Willowing is done to segregate fibres, remove dust impurities and to soften it. The raw wool procured from Changthang can have some dust to grazing in high pastures and these impurities are removed through multiple processes.

Cleaning

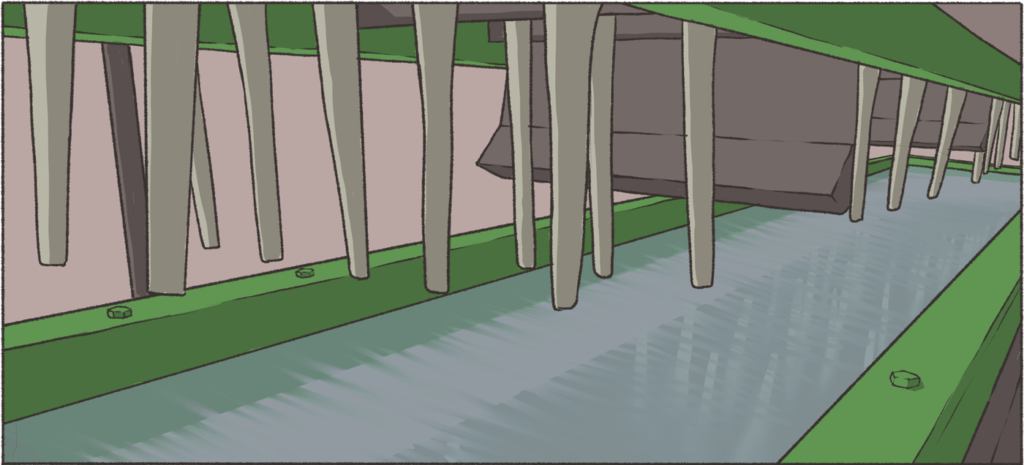

At the first level, dust, dandruff, vegetation particles and grease from the fleece are removed. The wool is then fed onto a series of cleaning bowls to further remove finer dust particles and impurities. Thorough washing of the wool is done to effectively remove mud and grease. The greasy substance and other impurities make up almost 40% of the total fleece weight.

Drying

After cleaning, the wool is kept for drying. It can be either put into a drying chamber where excess water is removed or laid outside for sun drying. After drying, wool is blended and conditioned to enhance the softness.

Dehairing

The scoured wool further undergoes the dehairing process where the soft Pashmina wool and the coarse hair are segregated. Finally, the clean dehaired wool is obtained and it is further detangled, blended to produce lumps of fine fibre ready for handcrafting. After dehairing, only a fraction of clean hair is usable for sale, cashmere production and value addition processes like weaving, spinning, yarn making.

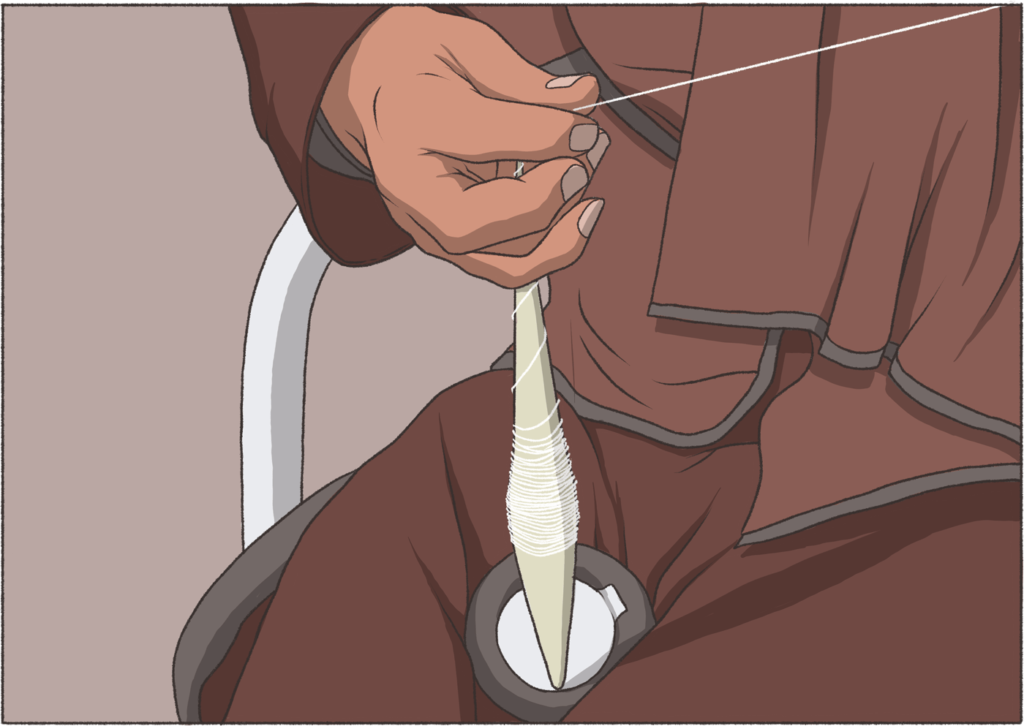

Spinning

After thorough cleaning and dehairing, the wool is ready for spinning; the fibre can be either machine-spun or handspun. Ladakhi artisans prefer hand-spinning and they use traditional willow spindle, “Phang” which produces ideal thread size. Handspun Pahsmina also renders more soft and durable products.

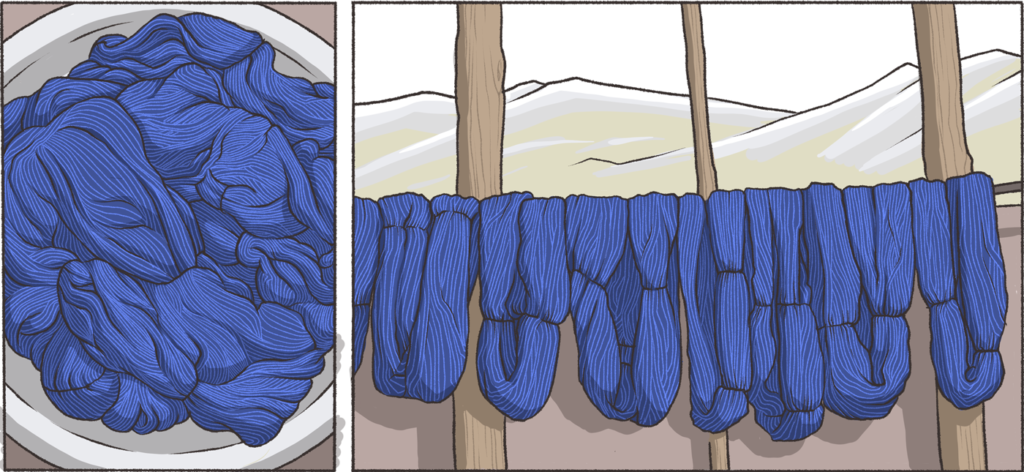

Dyeing

The yarn is then dyed. Earlier the shades were restricted to reds, maroons and browns. Ladakhi artisans are now exploring natural dyeing techniques where extracts of walnut shells, marigold flowers, saffron, madder, lac, arnebia, indigo and wild rose are used to give more vibrant hues to Pashmina products made in Ladakh.

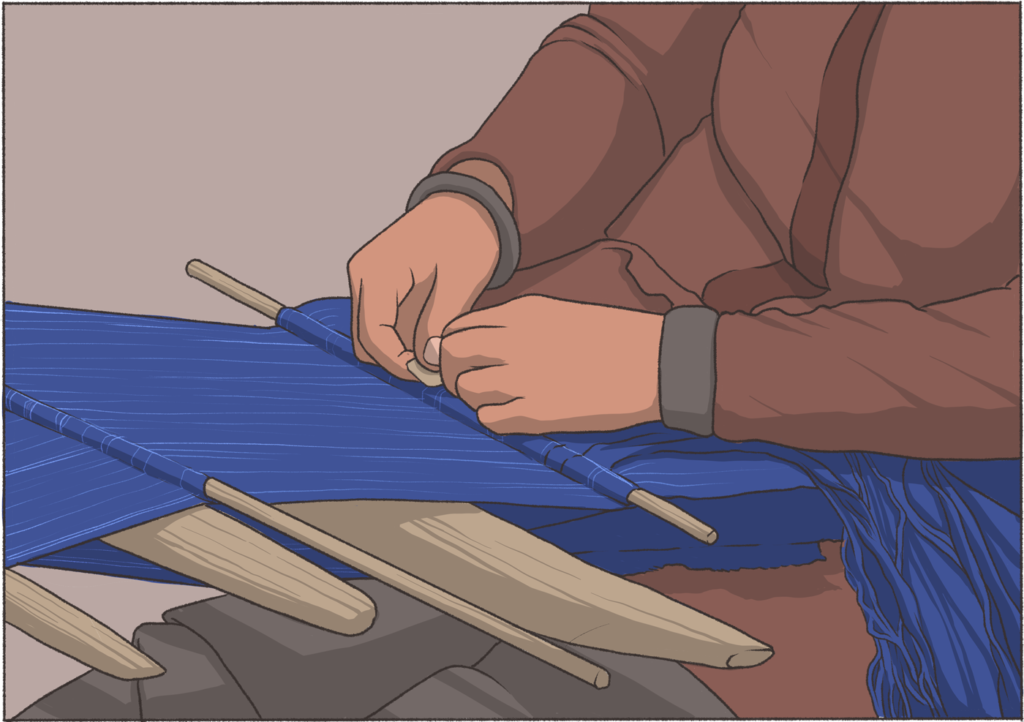

Weaving

Once spun and dyed, the weaving process begins either on the foot loom or the backstrap loom. Weaving wool is indigenous to many communities in Ladakh and it is deeply rooted in rich cultural traditions. Ladakhi artisans can hand weave exquisite designs and patterns with the Pashmina fibre!

Final Products

Handwoven products like Tsukden (carpet), rugs, Pashmina shawls and hand-knitted items like sweaters, stoles, gloves, hats are made followed by finishing and refining works. Products like Pashmina shawls/stoles are hand washed and hand pressed to retain the softness.

The Role of Pashmina

Pastoral activities involving Changra goats constitute a significant proportion of the culture and economy of Changpa community today.

Annual Pashmina Production

Changthang produces between 37,000 to 50,000 kg of pashmina annually

Pashmina turned into Finished Products

Less than 1,200 kg of raw pashmina is made into finished products within Ladakh

Livelihoods dependent on Pashmina

More than half of households of Changthang depend on sale of raw pashmina fibre

Annual Pashmina Production

Changthang produces between 37,000 to 50,000 kg of pashmina annually

Pashmina turned into Finished Products

Less than 1,200 kg of raw pashmina is made into finished products within Ladakh

Livelihoods dependent on Pashmina

More than half of households of Changthang depend on sale of raw pashmina fibre

This gap has a great potential for transformation to a sustainable, inclusive development in the region.

Meeting of Stakeholders (Dec 2019)

Goat herders, political representatives, government departments, youth groups, partner organisations, market experts came together to discuss creating finished products within Ladakh and branding Ladakh Pashmina in terms of sustainable, cultural heritage in both anthropological and ecological conservation.

Role in Ecological Balance

Increased demands of the multibillion dollar global cashmere industry are being felt across Central Asia.

Increased livestock numbers and grazing pressure has created a skew where wild herbivores contribute to less than 5% of the herbivore biomass across mountain ranges of Changthang and Central Asia.

Intense grazing can threaten the ecology of fragile high-altitude pastures.Intense grazing in Tibet has led to large scale desertification.

Traditional herding practices have ensured sustainable use of rangelands, allowing sustainable livestock to grow over generations.

They also allow for the coexistence of rare high altitude wildlife in the region, including the snow leopard, wolf, and their prey such as blue sheep, urial, ibex and argali.

Precarious survival of Tibetan gazelle in Changthang region, on the brink of extinction.